With great seafood comes great responsibility. This is a fact Norwegians know better than most.

Norway’s holistic, ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management and strict regulations that protect stocks, means that when you choose Norwegian seafood, you are choosing with the knowledge that the fish comes from sustainably managed stocks.

Norwegian fisheries management – how does it work?

Much is yet to be learned about the ecosystems below water, and not just about the fish. Sustainable ocean management is the promise of a continuous effort to act responsibly with the best data available.

In Norway, it starts with regulation and control – and with knowing as much as possible about our precious natural resources. It is an approach we are proud of, and one that is based on lessons learned the hard way.

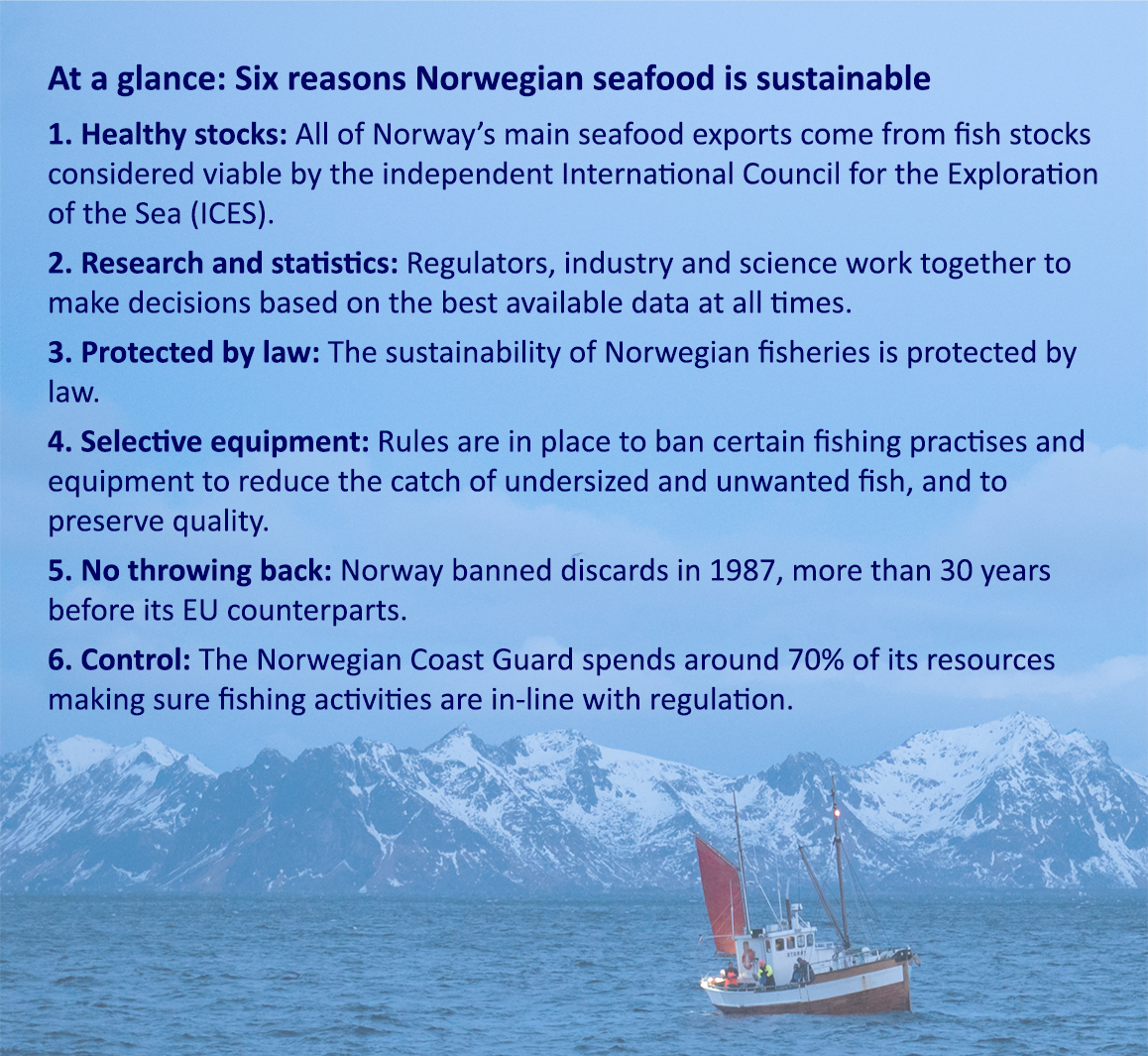

Our fish: Protected by law

In the 1980s, Norway experienced a serious fisheries crisis. Two of our most important fish stocks were close to depletion, the North East Arctic Cod, known to many as skrei, and Norwegian herring. The urgent need for stricter controls brought about a new law protecting our precious fish stocks. Today, this law is known as the Marine Resources act and has been updated to secure sustainable and economically sound management of Norwegian fish stocks now and for the future.

Research and statistics: Finding and counting fish

You cannot set accurate fishing quotas without first having a thorough understanding of the health of the seas. Norway spends a significant amount of time, money, and expertise on gathering the data that is needed to accurately set quotas for how much we – and other coastal states – can responsibly harvest from the various fish stocks each year. Scientific stock assessments and data collection is carried out by The National Institute of Marine Research. The data from these assessments is important for The International Council for The Exploration of the Seas (ICES) which prior to each fishing season, provides independent catch advice to the coastal states.

Protection: Not everything is up for grabs

Our thorough stock assessments enable us to protect younger fish classes from being caught, allowing new generations of fish to grow large enough before being subject to catching. This approach makes sense both ecologically and economically as the cost of “counting” is offset by future economic benefits. The Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries carries out trial fishing to identify what areas should be considered closed for a period of time to allow fish to spawn, grow and thrive. Closing of fisheries can also be a result of efforts to protect other vulnerable parts of the ecosystem, such as important corals. A ban of certain fishing equipment or methods may then become relevant.

Selective equipment: Sticking to your targeted catch

By-catch will always be a problem in fishing, but Norway has been taking steps for more than three decades to reduce the number of fish caught outside of quotas. We have rules guiding sorting grid size, mesh net size and the size of hooks used – all of which are designed to maximise targeted catch while making sure larger or smaller fish are spared and to protect the fragile ecosystems along our coast.

No throwing back: A ban on discards

Despite new and improved equipment, by-catch is inevitable. But in Norway, discards are banned. As well as being a highly wasteful practice, discarding by-catch makes it much harder to assess the health of the seas and the underlying condition of the stocks. Norway introduced the ban on discards in 1987. The EU recently introduced the same practice.

Control: More than just words

Regulation must be enforced, and Norway takes a multi-body approach to ensuring fishing policies are followed. The Norwegian Coast Guard spends around 70 percent of its resources making sure fishing activities are carried out at the right time, in the right areas and with the right equipment. The Directorate of Fisheries carries out regular inspections of fishing vessels arriving in port and at sea. Read more about controls and enforcement.

“The Norwegian model of seafood production is often acknowledged as best practice, and we are renowned across the world for the sustainable management of wild fisheries and responsible aquaculture production. By choosing seafood from Norway consumers can be assured they are eating some of the most sustainable and highest quality seafood there is.”

Renate Larsen

CEO, Norwegian Seafood Council

Norway – a global leader in sustainable seafood

Norway is the world’s second largest exporter of seafood, providing 37 million daily meals of seafood to 150 countries across the globe. Responsible management of our precious resources is at the very core of the Norwegian seafood industry.

Our seas are protected by law and the Norwegian method is so successful that we now manage some of the largest cod and herring stocks in the world, with other species also thriving in our waters. Our ecosystem-based approach also means that the seas are healthier as a result, with important corals being protected, for example. We have been the flag bearers on sustainability for decades, inspiring others to put laws in place to protect fish stocks and exporting our fisheries management expertise to underdeveloped fishing nations looking to build – and maintain – thriving and sustainable stocks.

The stats

It's not just talk – seafood from Norway's sustainable practices are backed up by hard data. Here are some grab-and-go facts at a glance:

- 2008: The year Norway ratified an updated ocean resource law making sustainability in fisheries a legal necessity, among many other things

- 70%: The share of time and resources the Norwegian Coast Guard spends making sure fishing activities are in-line with regulation

- 1987: The year Norway introduced a discard ban, becoming the first country to do so

- 28%: The increase in 2021 ICES recommended sustainable quota for Northeast Arctic cod, of which close to 100 percent of Norway’s cod exports come from

- 2,700,000: The number of tonnes of seafood exported by Norway in 2019

- 101,000: The length of Norway's coastline in kilometres – more than double the length of the equator